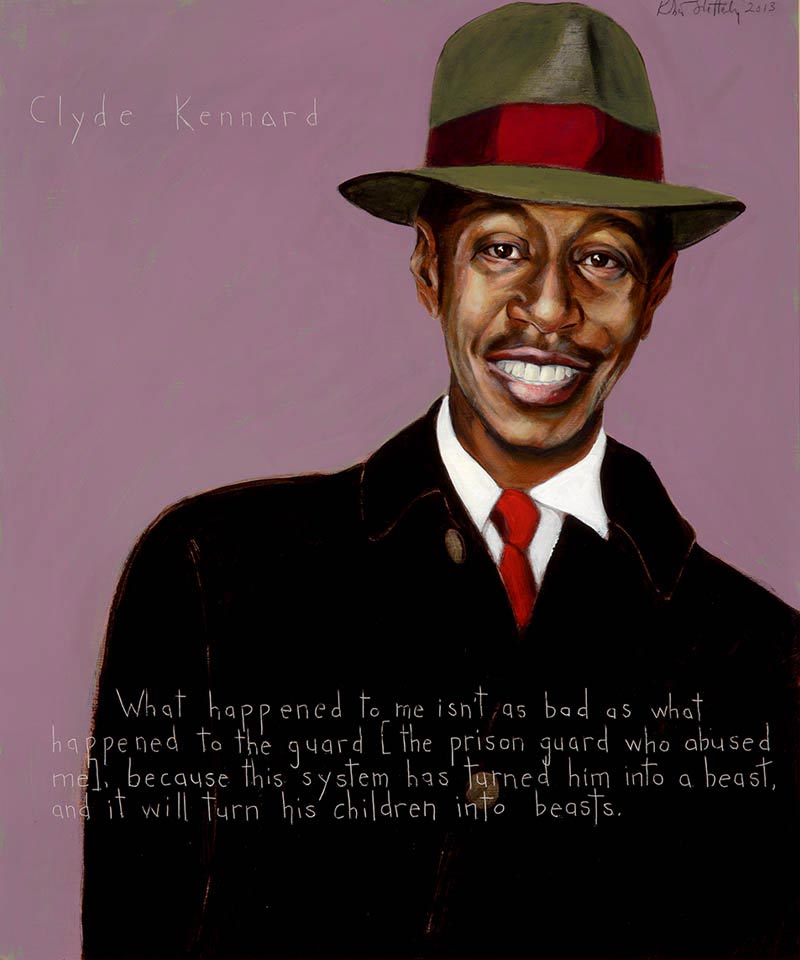

Clyde Kennard

Veteran, Student, Civil Rights Activist : 1927 - 1963

“What happened to me isn’t as bad as what happened to the guard [the prison guard who abused me], because this system has turned him into a beast, and it will turn his children into beasts.”

Biography

June 12, 1927: Clyde Kennard is born.

1955, 1958, 1959: Years that Kennard applied for enrollment to Mississippi Southern College.

September 25, 1960: Kennard is arrested on a false charge of stealing.

July 4, 1963: Kennard dies from cancer after his release from prison.

December 31, 2005: Investigative reporter Jerry Mitchell publishes his interview with the “witness” to Kennard’s crime who recants, clearing Kennard’s name.

May 16, 2006: Kennard is exonerated in the Circuit Court of Forrest County, Mississippi.

There are two Clyde Kennard histories.

The first is Kennard’s courageous persistence to defy the enforced segregation of Mississippi Southern College (now the University of Southern Mississippi). For these efforts, Kennard was framed on a false robbery charge and sent to prison. He died of cancer on July 4, 1963, just months after the sentence of the terminally ill man was commuted due to intense political pressure applied to the governor of Mississippi.

The second story is about the people who refused to let the injustice committed against Kennard stand uncorrected in the historical record and whose efforts resurrected an important and forgotten figure from the Civil Rights Movement.

Clyde Kennard was born in 1927 in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. At twelve, he followed an older sister north to Chicago to go to school. When he turned eighteen, he joined the military and served for seven years, first in Germany after World War II and then in the Korean War. After receiving an honorable discharge from the Army in the early 1950s, he enrolled at the University of Chicago. But three years into a degree in political science, his stepfather died and Kennard returned to Mississippi to help his mother run the farm he had bought her with the money he earned in the military.

Back in Mississippi, Kennard hoped to complete his degree. But the only college near the farm was the all-white Mississippi Southern College. Confident of his record at the University of Chicago, he decided to apply.

Kennard applied three times, in 1955, 1958, and 1959. The first time, Kennard was unable to fulfill the college’s requirement of five recommendations from graduates living in his county. Of course, all the graduates were white. The second time, the school president, conservative African Americans, and the governor of Mississippi collaborated to convince Kennard that the time was not right for integrating the college. He withdrew his application.

In September of 1959, Kennard decided that he would apply a third time. On his way to submit his application, Kennard stopped at a local diner where Raylawni Branch worked as a waitress. Branch would be one of two women who desegregated the college in 1965. On this day in 1959, however, she remembers customers in the diner trying to convince Kennard not to go to the school or, at least, to take someone with him. He refused their advice. The college president again rejected the application on a technicality, and as Kennard left the meeting he was met outside by two policemen who accused him of speeding and possessing alcohol in a dry country. Despite the lack of evidence, Kennard, who didn’t drink, was convicted of the charges, and fined $600 dollars.

Throughout this time, Kennard made his case for integration public, submitting letters to the editor of the The Hattiesburg American.

In 1958, Kennard argued that “merit be used as a measuring stick rather than race. We believe that for men to work together best, they must be trained together in their youth. We believe that there is more to going to school than listening to the teacher and reciting lessons. In school one learns to appreciate and respect the abilities of the other.”

In 1959, he tried to reassure his white neighbors: “[W]e have no desire for revenge in our hearts. What we want is to be respected as men and women, given an opportunity to compete with you in the great and interesting race of life. We want your friends to be our friends; we want your enemies to be our enemies; we want your hopes and ambitions to be our hopes and ambitions, and your joys and sorrows to be our joys and sorrows.”

In 1960, after his third attempt to enter the college and his arrest on bogus charges, Kennard was still not ready to give up the fight. He wrote to the editor that he had “done all that is within my power to follow a reasonable course in this matter … I have tried to make it clear that my love for the State of Mississippi and my hope for its peaceful prosperity is equal to any man’s alive. The thought of presenting this request before a Federal Court for consideration, with all the publicity and misrepresentation which that would bring about, makes my heart heavy. Yet, what other course can I take?”

In September of 1960, nine months after this last letter, Mississippi’s white establishment showed how far they would go to avoid a Federal lawsuit and keep the college segregated; Kennard was framed for masterminding the heist of twenty-five dollars worth of chicken feed. Convicted by an all-white jury, he was sentenced to seven years – one year for each $3.57 of feed – hard labor at Parchman Penitentiary, located two hundred miles north of Hattiesburg. Speaking at a rally in support of his friend, the NAACP activist Medgar Evers broke down in tears as he described the “mockery of judicial justice” in Kennard’s case.

The abuse of Kennard’s rights continued in prison. When he came down with cancer, he was refused treatment and forced to continue working in the fields despite his weakened physical state. Only after Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and others threatened to accuse the State of Mississippi of murder was the emaciated and terminally ill Kennard released. Dick Gregory paid for him to undergo treatment in Chicago. But it was too late to save the man who wanted a college degree. Kennard died less than a month after his friend, Medgar Evers, was murdered.

After his death, Kennard’s story burned in the anguished memories of friends and family but survived as little more than a footnote to the primary narratives of the civil rights movement.

Then in 1991 the Clarion-Ledger newspaper in Jackson, Mississippi published previously secret documents from the files of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, showing that Kennard had been framed. This was the first step toward restoring his name and righting the official history. Fourteen years later, Jerry Mitchell, an investigative reporter for the Clarion-Ledger whose work has helped put four Ku Klux Klan members in jail for crimes they committed in the 1960s, interviewed the black witness who, as a teenager, had testified against Kennard. The man admitted that Kennard had “nothing to do with the stealing of the chicken feed.” Mitchell proved what many had believed all along: Kennard’s desire to attend Mississippi Southern College was his only crime.

Kennard’s case came to the attention of a high school teacher in Chicago. Barry Bradford and his students teamed up with Steve Drizin, director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University’s School of Law, LaKeisha Bryant the president of the Afro-American Student Association at the University of Southern Mississippi, Dr. Joyce Ladner and Raylawni Branch, the woman who had served Kennard coffee on his way to apply to Mississippi Southern the third time and had gone on to an impressive career of her own. The team documented the case in favor of Kennard, discovered the legal arguments that could get the case back into court, and began to apply public pressure with the help of the former federal judge from Mississippi, Charles Pickering.

Finally, on May 16, 2006, the case that Steve Drizin called “one of the saddest of the civil rights era because he was silenced by ‘respectable’ people – academics, politicians, lawyers, prosecutors, judges, businessmen – all acting under the ‘color of law,’” finally ended up in the same court where the thirty-three-year-old Clyde Kennard had been convicted. The presiding judge in the Circuit Court of Forrest County, Robert Helfrich, declared, “It is a right-wrong issue. To correct that wrong I’m compelled to do the right thing and declare Mr. Kennard innocent.”

On the day of his exoneration, if he had lived, Clyde Kennard would have been less than a month shy of his seventy-ninth birthday.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.