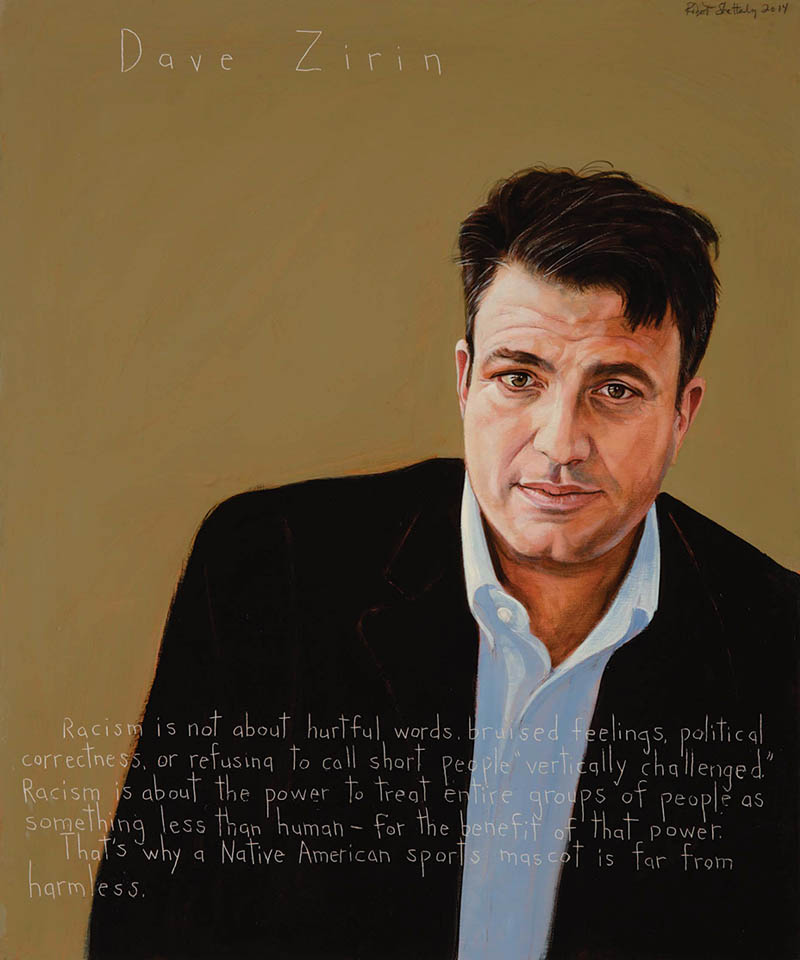

Dave Zirin

Sports Journalist : b. 1973

“Racism is not about hurtful words, bruised feelings, political correctness, or refusing to call short people ‘vertically challenged.’ Racism is about the power to treat entire groups of people as something less than human – for the benefit of that power. That’s why a Native American sports mascot is far from harmless.”

Biography

Recognized by Sport in Society and the Northeastern University School of Journalism for “Excellence in Sports Journalism.”

Named by the Utne Reader as one of 50 Visionaries Who Changing Our World.

Is a frequent guest on MSNBC, ESPN, and Democracy Now!

Is the Sports Editor for The Nation magazine.

In his 2011 book, Game Over, Dave Zirin concluded that Americans are being robbed by the owners of sports teams. “Now when many of us see the local stadium, we see a $1 billon real estate leviathan … that … has created a new species of fan: those who are paying for the stadiums [through taxes] but, unless they are working behind a counter, are unable to enter their gates.” As Zirin explores the intersection of sports and politics, he maintains a sharp focus on the money trail, particularly the billionaire owners who further enrich themselves by relying on middle-class Americans’ taxes to fund their massive stadiums.

Zirin was born and raised in New York City. Like many boys and girls in America, he grew up participating in organized sports and following his local teams: the Knicks, Mets, and Rangers. One of his favorite players growing up was New York Giants linebacker Lawrence Taylor, a man who revolutionized the position with his athletic and aggressive play.

Some years later, in 1996, the story of an NBA player named Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf caught Zirin’s attention. Rauf refused to come out of the locker room for the playing of the national anthem, objecting to the use of sports for nationalistic ends. When asked about it, Rauf said that the flag may represent freedom and democracy to some, but to others it represents tyranny and oppression. Rauf’s career did not last much longer.

Zirin listened to the talking heads on ESPN say that Rauf must be one of those activist athletes, like Billie Jean King, Muhammad Ali, or Arthur Ashe. He wondered what an “athlete activist” was, so he dug into books and started learning. This moment changed his career. He was deeply influenced by Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of United States and would go on to write A People’s History of Sports in the United States.

Most people claim that sports and politics don’t mix or that they have never thought about how they do. As a pioneering sports journalist, Zirin began to challenge readers to think about the connection between sports and social and economic justice. In fact, Zirin came to believe that you can’t talk about the American civil rights movement without mentioning Jackie Robinson or Muhammad Ali, or about gay rights without talking about Billie Jean King and Martina Navratilova.

Zirin writes about how the business relationships between the players and the owners of the sports franchises are affected by the fact that many professional athletes come from ghettos in the United States or poor countries in Latin America. According to Zirin, during the 2011 NBA lockout, as former commissioner of the NBA David Stern “sat across the table from a constellation of the league’s stars, he became, per his usual style, openly contemptuous of the players’ … inability to understand the financial challenges faced by ownership.” Zirin writes of the “plantation overseer” dynamic found in college and professional athletics in the United States and sees the racism in sports as an extension of the larger society’s culture: “If we accept that racism is still alive and well outside the arena, then sports would have to exist in a hermetically sealed, airtight environment in order to remain uninfected. Impossible.”

In Game Over, Zirin goes beyond a critique of current practices to historicize the culture of sports in America, linking it to deep political and societal trends. He writes, for example, that, ” [Teddy] Roosevelt saw tough athletic training as a way to build a basis for a new American century. … Ideas like Muscular Christianity were about preparing the United States for empire. During this period, the U.S. set out to invade the Philippines, Latin America, and the Caribbean; the value of sports was deeply tied to imperialist notions of conquest and missionary zeal.” He then reconnects these historical insights to the present: “[Sports] has always been about selling a supremely militaristic, dominant image of the United States back to ourselves. After all, who tossed the coin at the 2009 Super Bowl? It wasn’t John Elway or Joe Montana. It was General David Petraeus.”

As Zirin focuses on both professional and amateur sports, he reminds us that the critique of the college athletics business is not new. He writes, “A century ago, the great intellectual (and sports fan) W. E. B. Du Bois wrote about the corrosive effect college athletics was beginning to have on the health and culture of academic institutions. If schools are reduced to football factories where classes just happen to be taught, everyone loses, particularly the unpaid athletes who generate millions and are told they are being paid with academics.”

Zirin wishes that more athletes would learn to use their celebrity to address social justice issues when they talk to the media, believing that the impact could be significant. He says, as it stands now, “… whether we want to admit it or not, athletes are role models – of obedience to authority, to hierarchy; of promotion of groupthink over individual opinion; or a kind of social discipline that pervades society.¨ Commenting on the potential power of the popular quarterback for the Washington Redskins, Robert Griffin III, Zirin writes, “If RG3 held a press conference tomorrow and said, “‘Look, I love this team, I love this town, but I feel like the Redskins is a racist name and I’d like to rename the team the Washington Subway Sandwiches,’ people might do it! That’s how much people love the guy!”

Zirin remains a fan of the athletes and the games but has come to dislike the corporate packaged, sterile business of sports. To him, pointing out how sports are used to promote militarism, calling out racist practices where they exist, and exposing the misuse of money does not detract from his appreciation of individual and team athletic achievement.

As of 2020, Zirin has written ten books, made two movies, and has contributed to numerous magazines, including The Nation, SLAM magazine, and The Progressive. He also publishes a blog called Edge of Sports.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.