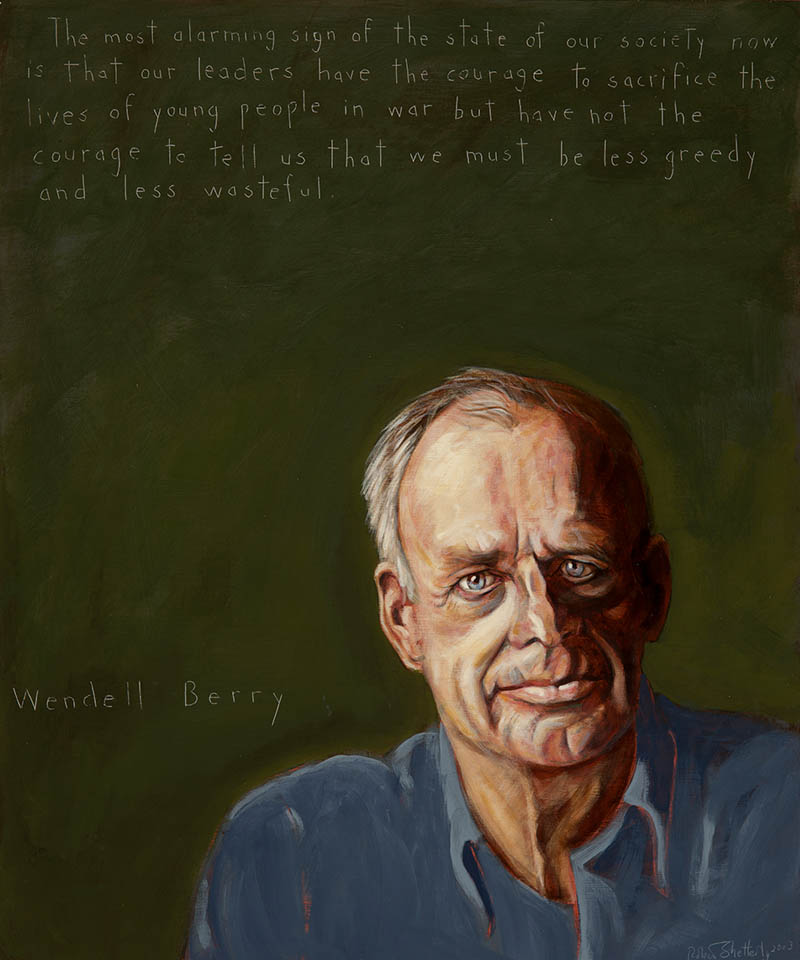

Wendell Berry

Farmer, Essayist, Conservationist, Novelist, Teacher, Poet : b. 1934

“The most alarming sign of the state of our society now is that our leaders have the courage to sacrifice the lives of young people in war but have not the courage to tell us that we must be less greedy and wasteful.”

Biography

Born in 1934, Wendell Berry is the first of four children of Virginia Erdman Berry and John Marshall Berry, a lawyer and tobacco farmer. Both the Erdmans and the Berrys have farmed in Kentucky’s Henry County for at least five generations.

Wendell earned a B.A. and M.A. in English at the University of Kentucky, and in 1958, pursuing his love of writing, he attended Stanford University’s creative writing program as a Wallace Stegner Fellow, studying under Stegner in a seminar that included Edward Abbey, Larry McMurtry, Robert Stone, Ernest Gaines, Tillie Olsen, and Ken Kesey.

In 1965, Berry purchased a farm in Lanes Landing, Kentucky, near his parents’ birthplaces and began growing corn and small grains on what eventually became a 125-acre homestead. Berry has farmed, resided, and written at Lane’s Landing up to the present day. One can read about his early experiences on the land and about his decision to return to it in essays such as “The Long-Legged House” and “A Native Hill.” He has written at least twenty-five books of poems, sixteen volumes of essays, and eleven novels and short story collections. His writing is grounded in the notion that one’s work ought to be rooted in and responsive to one’s place.

For decades, Berry, as poet, essayist, fiction writer, and farmer, has advocated personal activism on behalf of the environment. He has written that there should not be a “split between what we think and what we do. Once our personal connection to what is wrong becomes clear, then we have to choose: we can go on as before, recognizing our dishonesty and living with it the best we can, or we can begin the effort to change the way we think and live.” What Berry believes is reflected in how he conducts his life. He has been an activist in numerous areas of society. At the 1968 University of Kentucky conference on the War and the Draft, in “A Statement Against the War in Vietnam” Berry said: “I have come to the realization that I can no longer imagine a war that I would believe to be either useful or necessary. I would be against any war.” And in his essay, the “Failure of War” (1999) he wrote, “How many deaths of other people’s children . . . are we willing to accept in order that we may be free, affluent, and (supposedly) at peace? To that question I answer: None. . . . Don’t kill any children for my benefit.”

In 1979 he participated in non-violent civil disobedience against the construction of a nuclear power plant in Marble Hill, Indiana. His 2003 essay titled “A Citizen’s Response to the National Security Strategy of the United States,” a critique of the George W. Bush administration’s post 9/11 international strategy that justified preemptive war, was published as a full-page advertisement in The New York Times. In it he asserted that “The new National Security Strategy published by the White House in September 2002, if carried out, would amount to a radical revision of the political character of our nation.”

In 2009, Berry, along with Wes Jackson, president of The Land Institute and Fred Kirschenmann of The Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture, gathered in Washington D.C. to promote the idea of a 50-Year Farm Bill claiming that “We need a 50-year farm bill that addresses forthrightly the problems of soil loss and degradation, toxic pollution, fossil-fuel dependency and the destruction of rural communities.” Also in 2009, he joined with 38 writers, to publicly request Kentucky Governor and Attorney General to impose a moratorium on the state’s death penalty. In that same year, he spoke out against the National Animal Identification System, which required that independent farmers pay the cost of registration devices for each animal while large, corporate factory farms pay by the herd. Said Berry, “If you impose this program on the small farmers, who are already overburdened, you’re going to have to send the police for me. I’m 75 years old. I’ve about completed my responsibilities to my family. I’ll lose very little in going to jail in opposition to your program – and I’ll have to do it.”

Opposing the use of coal as an energy source, in 2009 Berry joined over 2,000 others in non-violently blocking the gates to a coal-fired power plant in Washington, D.C., and later that year combined with several non-profit organizations and rural electric co-op members to petition against and protest the construction of a coal-burning power plant in Clark County, Kentucky. As a result, in 2011 the Kentucky Public Service Commission cancelled the construction of this power plant. On September 28, 2010 Berry participated in a rally in Louisville during an EPA hearing on how to manage coal ash. Berry said, “The EPA knows that coal ash is poison. We ask it only to believe in its own findings on this issue, and do its duty.” Berry, with fourteen other protesters, spent the weekend of February 12, 2011 locked in the Kentucky governor’s office demanding an end to mountaintop removal coal mining.

Through whatever he is writing, Berry’s message is constant: humans must learn to live in harmony with the natural rhythms of the earth or perish. In his opinion, we must acknowledge the impact of agriculture to our society. Berry believes that small-scale farming is essential to healthy local economies, and that strong local economies are essential to the survival of the species and the well-being of the planet. In an interview with New Perspectives Quarterly editor Marilyn Berlin Snell, Berry explained: “Today, local economies are being destroyed by the ‘pluralistic,’ displaced, global economy, which has no respect for what works in a locality. The global economy is built on the principle that one place can be exploited, even destroyed, for the sake of another place.” He believes that besides relying on chemical pesticides and fertilizers, promoting soil erosion, and causing depletion of ancient aquifers, the growth of agribusiness has been a major cause of the disintegration of communities, driving many small farms out of existence, destroying rural communities in the process along with their moral fiber and wisdom.

Wendell Berry lives up to his own standards, both privately and publicly. He uses horses to work his land and employs organic methods of fertilization and pest control. In 2010 he withdrew personal papers he had donated to the University of Kentucky because he objected to a decision to name a basketball-players’ dormitory the Wildcat Coal Lodge. “The University’s president and board have solemnized an alliance with the coal industry, in return for a large monetary ‘gift,’” he wrote. “That…puts an end to my willingness to be associated in any way officially with the University.” He intends to transfer his papers to the Kentucky Historical Society.

Related News

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.