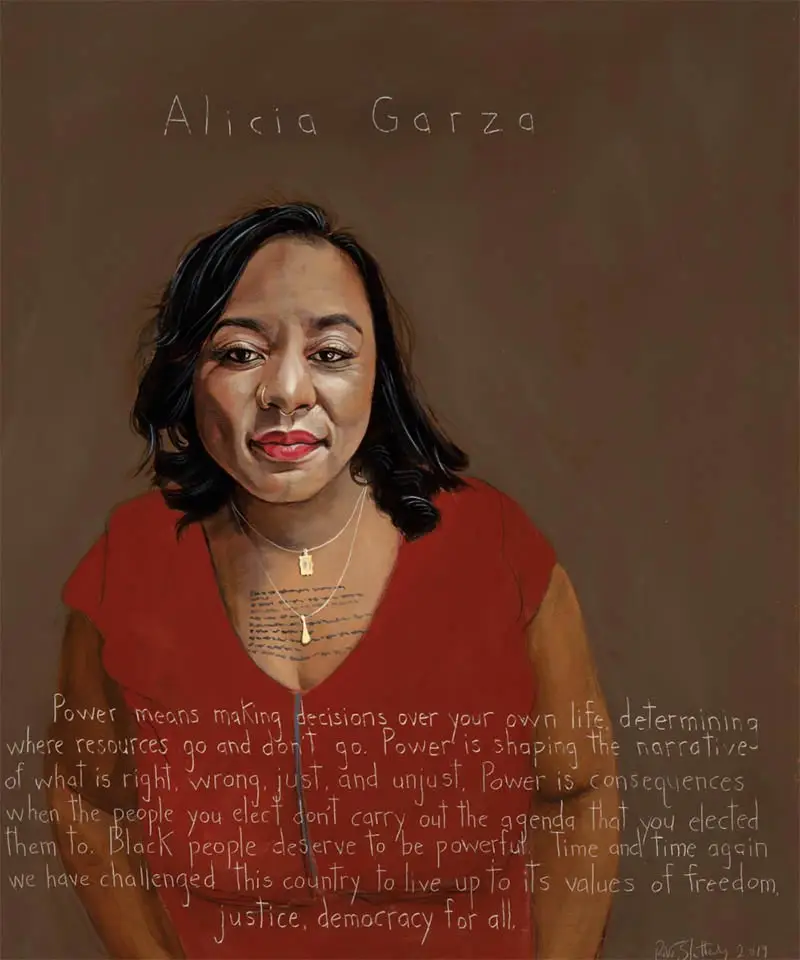

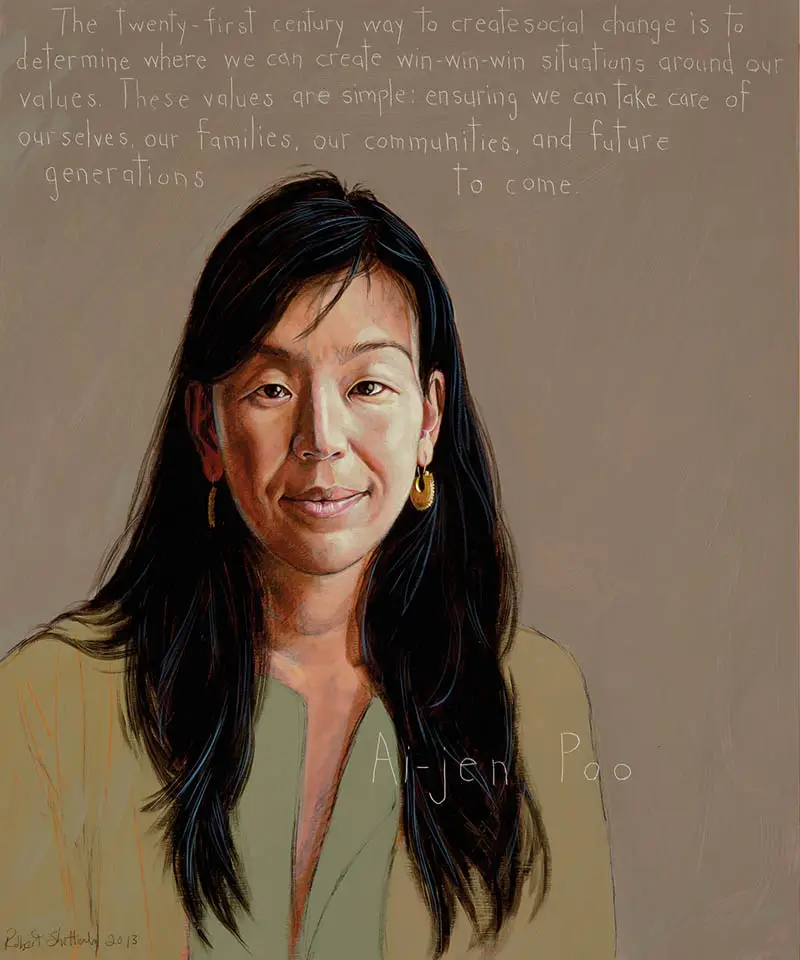

Ai-jen Poo

Ai-jen Poo

Organizer of Domestic Workers : b. 1974

“The twenty-first century way to create social change is to determine where we can create win-win-win situations around our values. These values are simple: ensuring we can take care of ourselves, our families, our communities, and future generations to come.”

Speaking Truth to Youth

Organizer of domestic workers Ai-jen Poo describes how the many elders and strong women in her life inspire her to work to honor and protect the caregivers in our country.

Biography

2000: Co-Founded Domestic Workers United

2010: Passage of Domestic Workers Bill of Rights

2010: Becomes the director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance

2011: Recipient of Independent Sector’s American Express NGen Leadership Award

2012: Named to Newsweek’s 150 Fearless Women list and TIME’s list of the 100 Most Influential People in the World

In 2012, Ai-jen Poo was named one of Time magazine’s most influential people and appeared on Newsweek’s list of “150 Fearless Women.” As founder and president of the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA), Ai-jen Poo has been catapulted into the spotlight by the success of her fight for the rights of domestic workers.

As much as the NDWA’s achievements, it ‘s Poo’ s unusual organizing philosophy that has caught people’s attention. For Poo, organizing is not about confrontation, it is about love:

“I believe that love is the most powerful force for change in the world. I often compare great campaigns to great love affairs because they’re an incredible container for transformation. You can change policy, but you also change relationships and people in the process.”

This emphasis on love distinguishes Ai-jen Poo from many twentieth-century American labor organizers who used a more confrontational – even violent – approach to win worker rights. For Poo, social change is more powerful when it comes from a place of mutual compassion, which makes special sense in this casesince domestic work is about taking care of others.

In an interview with The Sun magazine, Poo explained that a domestic worker is anyone who works in someone’s home. Domestic workers include nannies, cooks, housekeepers, and eldercare providers who often play the additional roles of tutor, chauffeur, or confidante. According to Poo, “Theirs is the work that makes all other work possible, because without it many professionals could not go to their jobs.”

Though essential, the work is usually invisible because it takes place behind the walls of someone’s home. Typically, this work is done by women, and those women are often ethnic minorities or undocumented immigrants. Employers can easily take advantage of these isolated employees who have no one to tell if they are treated unfairly. Says Poo, “I have heard about employers who have kept workers’ passports or not paid them for months or fired them for calling in sick or becoming pregnant. In between are the employers who do not respect boundaries, who come home at eight when they said they would be home at six; meanwhile the worker’s own family is waiting for a meal.”

The workers who organize with Ai-jen Poo are given the space to tell their stories and have their individual voices heard. Though domestic work has been undervalued by society, enabling and emphasizing the connection between domestic workers and their employers has led to major social change in the form of legislation and improved working conditions.

However, this loving approach doesn’t mean that conflict has been removed from the activism:

“I think that you can love someone and be in conflict with them,” [Poo] says. “And I think that it’s the same thing when we’re trying to transform a fundamentally unequal society. There’s a level of discomfort and conflict that has to happen in order for us to achieve a more loving fate.”

When Poo started organizing domestic workers in 2000, many thought she was taking on an impossible task. Domestic workers were too dispersed, spread out over too many homes. Even Poo had described the world of domestic work as the “Wild West.”

Poo’s first big breakthrough with the NDWA happened on July 1, 2010, when the New York state legislature passed the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights. The bill legitimated domestic workers and gave them the same lawful rights as any other employee, such as vacation time and overtime pay. Though the bill was considered a major victory, the NDWA did not stop there, expanding operations to include seventeen cities and eleven states.

Poo grew up in a family that taught her the value of social justice. Her parents, a scientist and a doctor, immigrated to the United States from Taiwan, where her father was a pro-democracy activist. After growing up in California and Connecticut, Ai-jen Poo’s career as an activist began when she was majoring in women’s studies at Columbia University. She joined one hundred fellow students in an occupation of the university library demanding that Columbia develop a new curriculum reflecting the rich diversity of the student body. As a result of the protest, Columbia established a Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race.

This experience gave Ai-jen Poo confidence. “Working with a really diverse group of students around our shared goals gave me a sense of how powerful campaigns can be if they’re strategic—how it is possible to really make change.”

After college, Poo took a job at the Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence, where she learned about the vulnerability of domestic workers. Inspired by the women she met, she co-founded New York City’s Domestic Workers United in 2000. Eventually, the DWU grew into the NDWA, which operates nationwide.

September 2013 was a significant month for the NDWA. On September 17, the United States Department of Labor announced that they were “extending the Fair Labor Standards Act’s minimum wage and overtime protections to most of the nation’s workers who provide essential home care assistance to elderly people and people with illnesses, injuries or disabilities.” On September 27, California governor Jerry Brown signed the California Domestic Workers Bill of Rights. In addition to these victories, the movement keeps spreading; several other states plan to vote on similar laws in the future.

In 2014, Poo was awarded a MacArthur fellowship, “a five-year grant … to fund her vibrant, worker-led movement.” In June 2019, a National Domestic Bill of Rights was introduced in the U.S. Congress. As of late 2020, NDWA membership had expanded to over sixty affiliated organizations and local chapters and thousands of individual members, while nine states and two cities had passed laws protecting domestic workers.

Thanks to Ai-jen Poo and her activism of love, the domestic worker movement is growing across the country, inspiring domestic workers and their allies to stand up for fair treatment and better working conditions.

Related News

Related Portraits

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.