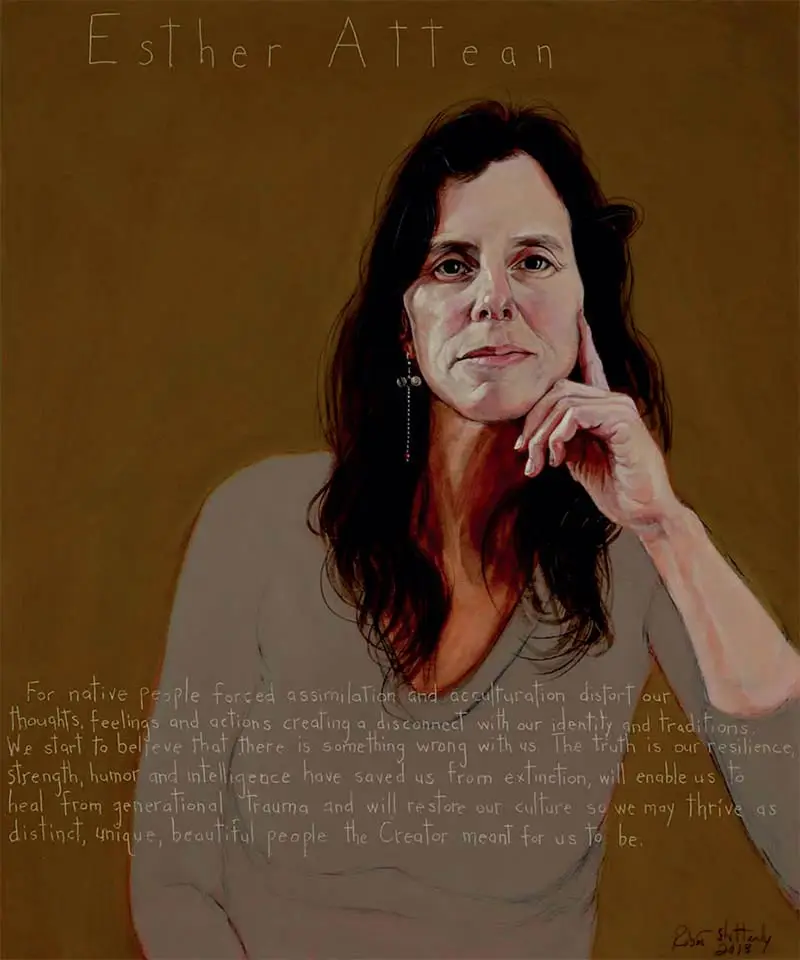

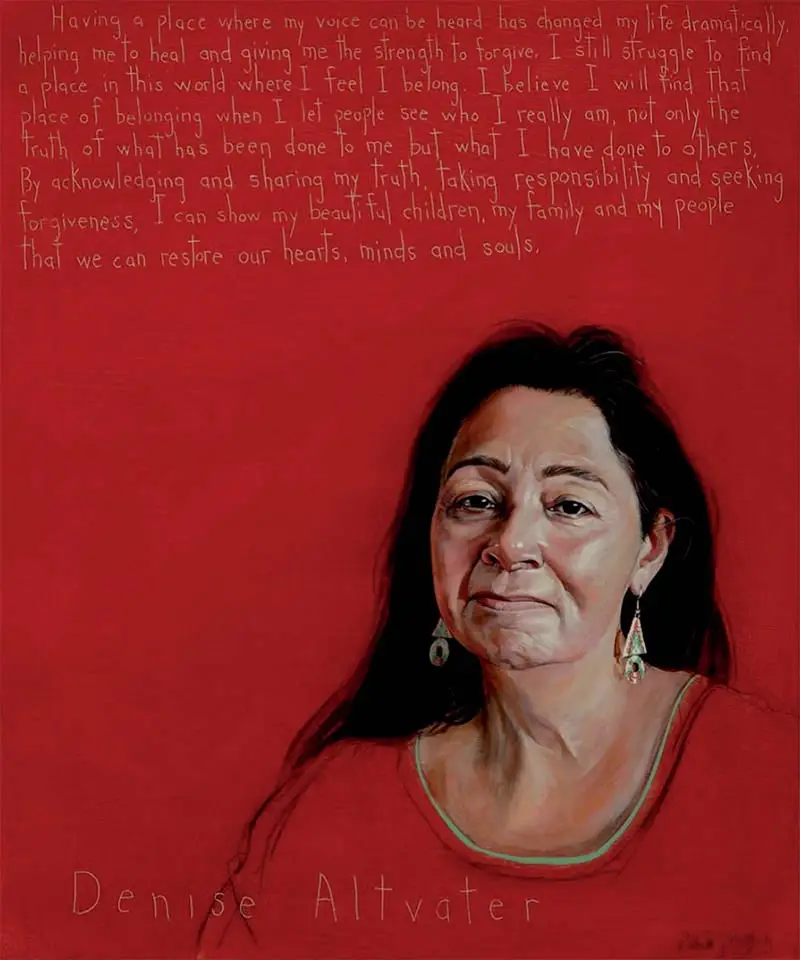

Denise Altvater

Activist, Community Organizer, Co-Founder of the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission process : b. 1959

“Having a place where my voice can be heard has changed my life dramatically, helping me to heal and giving me the strength to forgive. I still struggle to find a place in this world where I feel I belong. I believe I will find that place of belonging when I let people see who I really am, not only the truth of what has been done to me but what I have done to others. By acknowledging and sharing my truth, taking responsibility and seeking forgiveness, I can show my beautiful children, my family and my people that we can restore our hearts, minds and souls.”

Biography

2001 Ford Foundation Award, “Leadership for a Changing World”

2004 University of Maine, Mary Ann Harman Award recipient, Maine Women’s Fund Award.

2012 “Planetary Chaplain of the Year” Award recipient, by the Chaplaincy Institute of Maine.

2013 recipient of the Courageous Love Award, given by the Winthrop Area Ministerial Association.

Denise’s mother wasn’t home when the Maine Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) workers arrived at her house. They took seven-year-old Denise and her five sisters, threw the girls’ clothes into garbage bags, packed them all into two station wagons, and drove away from the Passamaquoddy reservation at Pleasant Point. No one explained to them what was happening.

Denise and her sisters spent the next four years in a foster care nightmare. They were raped, deprived of food, locked in a cold basement with rats overnight, made to stay in a urine soaked bed for twenty-four hours at a time and to kneel on broom handles as punishment. When Denise and her sisters tried to explain what was happening, the social workers didn’t believe them, and the brutal punishments increased.

At age 11, Denise was placed in a kinder home, but she and her sisters were split up into two different families. Though life was better, the pervasive sense of not belonging continued. The foster family discouraged her from telling anyone she was a Native American. Denise says now that, “the trauma was in the taking.” Regardless of the environment they were thrust into or the conditions of the home from which they were taken, being severed from culture, community, language, traditions, and her mother created a huge psychic fracture. The abusive placement just added to the loss and emotional and spiritual damage.

Seven years after being taken, social services finally reunited Denise with her mother. But Denise no longer wanted to go back to the reservation, and she was raped shortly after arriving – something she never told anyone since there was no counseling or support for that kind of trauma. She attended Lee Academy in Maine, where she boarded during the week and came home to the reservation on weekends. After she made the cheerleading squad at Lee, she returned to her room to find her cheerleading uniform cut to shreds. A sign had been left that read, “Not for Indians.” She left Lee and never went back.

Denise then entered Eastport High School, where the native students sat in the back of the class and were essentially ignored. The racism was intense and she dropped out during her junior year. When she was sixteen, Denise’s boyfriend, Brian, encouraged her to go back to her second foster family and regain the stability she had there. It didn’t work. Soon she was back on the reservation, with no supervision, “let go wild.”

Just before turning seventeen, Denise intentionally got pregnant with Brian, who was nineteen, and they married. She thought it was a way to connect with something. Denise worked for the tribe with no high school diploma. She took college classes and trainings whenever she could, but no one knew she didn’t have her high school degree. By age twenty-seven, she couldn’t stand the secret any longer and told a nun who ran the local school. Sister Maureen helped Denise get her high school diploma and then encouraged her to enroll at University of Maine at Machias.

The Quaker organization, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), hired Denise in 1992 to create the AFSC Wabanaki Program. This marked a significant change in her life, as she was able to serve the youth in her community in the ways she knew would best meet their needs; she knew what she had needed at their age. The programs and experiences she created for Wabanaki youth emphasized a renewal of cultural traditions, boosted social and job skills, and helped native youth deal with discrimination, domestic abuse, and alcohol and drug addiction.

When the tribal youth at Sipayik – the Pleasant Point reservation in Maine – wanted to learn to drum and perform native ceremonies, Denise took them to Canada to learn from Passamaquoddy and MicMac First Nations elders. There, Denise and Brian reconnected with their Wabanaki heritage. In her mid-thirties Denise participated in a Naming Ceremony led by a MicMac elder, David Gehue. The name she was given, “Wiciw Ckuwatoni Ehpit,” means: “One Who Rises With The Sun.” By taking this name she made a commitment to never use alcohol or drugs again, to never commit suicide or homicide, and to live in a sacred way.

Denise has been a leading voice in raising the alarm about the devastating impact of Oxycontin in Maine, which has the nation’s second-highest per-capita abuse of this highly addictive, legal drug. And her work to address the racism of the criminal justice system in Maine has led to appointments to the Maine State Board of Visitors, the Maine Indian Tribal State Commission (MITSC), the Wabanaki Criminal Justice Commission (CJC), and the Department of Corrections Advisory Group.

Perhaps Denise’s greatest contribution to the truth and reconciliation process happened in 1999. When Maine was found to be out of compliance with the federal Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), DHHS reached out to the Wabanaki communities for help. Denise stepped forward and told her story for a training film about the experiences of Wabanaki people who had been in state foster care. Using this film, she went on to help train more than five hundred DHHS workers in Maine on the importance of the ICWA. Denise did not receive the emotional and psychological support she needed when she began sharing what happened to her as a child, which led to five hospitalizations from the physical and emotional impact of repeatedly uncovering her history. But in the telling of the trauma of being taken from her culture, she has helped the next generation by exposing the truth of many Wabanki peoples’ lives.

The painful history of the Wabanaki people has remained largely invisible to the non-native community. Denise’s willingness to share her personal experiences has made it possible for many to understand the painful truth of what happened to so many native children in our child welfare system. Denise’s generous sharing of her personal truth helped make the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in Maine a reality.

The three goals of the Maine TRC are: truth – to uncover and acknowledge the truth about what happened to Wabanaki children and families involved with the Maine child welfare system; healing – to create opportunities to heal and learn from the truth; and change – to collaborate to operate the best child welfare system possible for Wabanaki children and families. The film Dawnland documents TRC’s historic work.

Related Portraits

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.