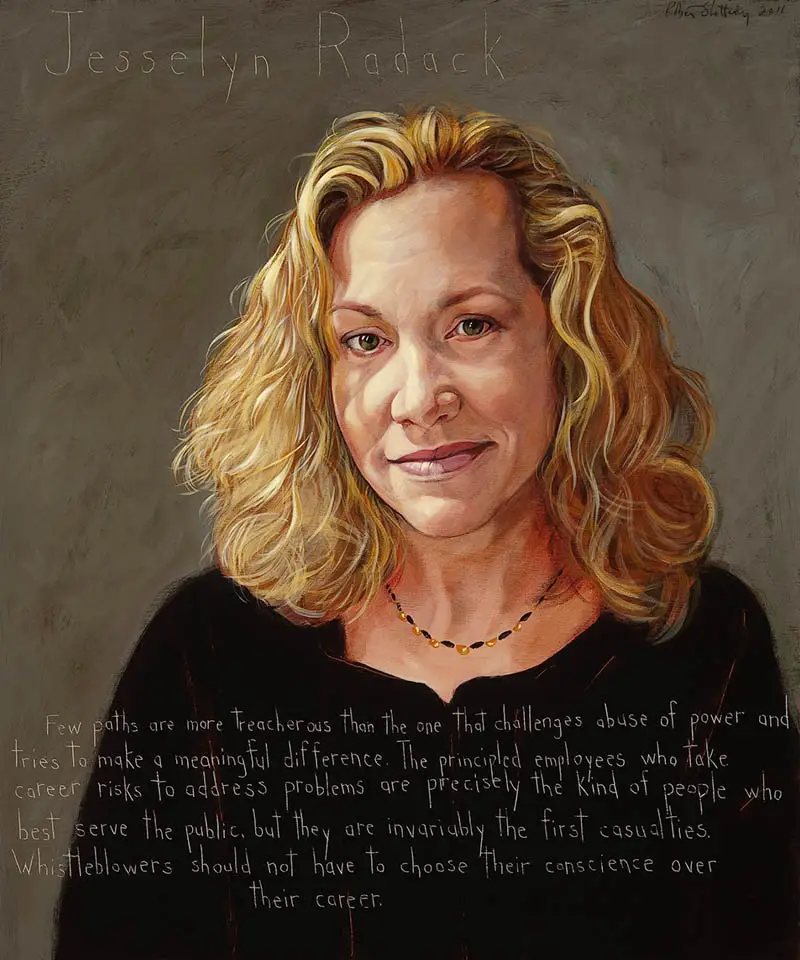

Jesselyn Radack

Jesselyn Radack

Lawyer, Whistleblower, Defender of Whistleblowers : b. 1970

“Few paths are more treacherous than the one that challenges abuse of power and tries to make a meaningful difference. The principled employees who take career risks to address problems are precisely the kind of people who best serve the public, but they are invariably the first casualties. Whistleblowers should not have to choose their conscience over their careers.”

Biography

Jesselyn Radack graduated from Yale Law School in 1995 and joined the Justice Department through the Attorney General Honors Program. She practiced constitutional tort litigation for four years before becoming a Legal Adviser to the Professional Responsibility Advisory Office.

Shortly after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Radack received an inquiry from a Justice Department counterterrorism prosecutor asking about the ethical propriety of interrogating—without a the presence of a lawyer—a U.S. citizen who had allegedly fought with the Taliban in Afghanistan. The prisoner was “American Taliban” John Walker Lindh.

The prosecutor told Radack that Lindh’s father had retained counsel for his son. Radack responded that interrogating him without his lawyer was not authorized by law. Despite her counsel, the FBI proceeded to question Lindh.

A few days later, the counter-terrorism prosecutor called Radack again. She advised that Lindh’s confession, obtained without the presence of a lawyer, might have to be sealed and only be used for national security and intelligence-gathering purposes, not criminal prosecution.

Five weeks after the interrogation, Attorney General John Ashcroft announced that a criminal complaint was being filed against Lindh. “The subject here is entitled to choose his own lawyer,” Ashcroft said, “and to our knowledge, has not chosen a lawyer at this time.” Radack knew that what Ashcroft said was not true, that Lindh did indeed have a lawyer. Three weeks later, Ashcroft announced Lindh’s indictment, saying that his rights “have been carefully, scrupulously honored.” This statement was contradicted by a photograph from Lindh´s time in U.S. custody that was sent around the world; in it Lindh was naked, blindfolded and bound to a board with duct tape.

On March 7, 2002, the lead prosecutor in the Lindh case emailed Radack to tell her that there was a court order for all of the Justice Department’s internal correspondence about Lindh’s interrogation. He said that he had two of her emails and wanted to make sure he had everything.

Radack became concerned for two reasons: First, because she had not been told about the court order, and, second, because she had written more than a dozen relevant emails about the Lindh case and the Justice Department had turned over only two of them to the prosecutor. Neither of the emails the prosecutor had obtained reflected her fear that the FBI’s actions had been unethical and that Lindh’s confession, which formed the basis for the criminal case, might not be admissible in the trial.

Radack checked the hard-copy file and found that it had been purged. With the assistance of technical support, Radack then recovered fourteen emails from her computer archives, gave them to her boss, and resigned. She also took copies of the emails home with her in case they “disappeared” again.

As the Lindh case proceeded, the Justice Department continued to swear that it knew nothing of the fact that Lindh already had a defense attorney at the time of his interrogation. Radack heard a National Public Radio broadcast stating that the Justice Department had never taken the position that Lindh was entitled to counsel during his interrogation. She did not think the Department would have had the temerity to publically contradict its own court filings if her missing emails had been part of the record.

After hearing that broadcast and in accordance with the Whistleblower Protection Act, Radack sent the emails to a magazine reporter who had been interviewed in the radio piece. He then wrote an article about the missing emails.

On the morning Lindh’s suppression hearing (to determine the admissibility of his confession) was due to begin and three weeks after Radack’s disclosure of the emails became public, Lindh pleaded guilty to two relatively minor charges. The surprise deal, which startled even the judge, averted the crucial evidentiary hearing that would have probed the facts surrounding his interrogation—which Radack had advised against—and determined whether his statements could be used against him at trial—she had said they couldn´t be used. Commentators widely agreed that the Lindh prosecution had “imploded.”

In retaliation, the government unleashed the full force of the entire executive branch against Radack. Among other things, the Justice Department placed her under criminal investigation, although she was never told what charges she was facing. Based on a secret report she was not allowed to see, the Justice Department also referred her for discipline to the state bar associations where was licensed to practice law, and placed her on the “No-Fly List.”

Eventually, the criminal case closed with no charges ever being brought. The Maryland State Bar Association dismissed the charges against Radack in 2005. She was elected to, and served on, the D.C. Bar Legal Ethics Committee from 2005-2007, despite the fact that the charges against her were still pending at the time.

Radack tells her story in her memoir, Traitor: The Whistleblower and the “American Taliban” (2012) and in the documentary Silenced (2014).

She represented whistleblowers as the director of Homeland Security and Human Rights at the Government Accountability Project from 2008-2015, then went on to become the director of the Whistleblower and Source Protection Program (WHISPeR) at the Institute for Public Accuracy’s ExposeFacts. She has represented dozens of well-known whistleblowers, including John Kiriakou, Edward Snowden, Thomas Drake, and Daniel Hale. She frequently writes and speaks on the topics of whistleblowing, torture, surveillance, Internet freedom, and privacy on television and in print.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.