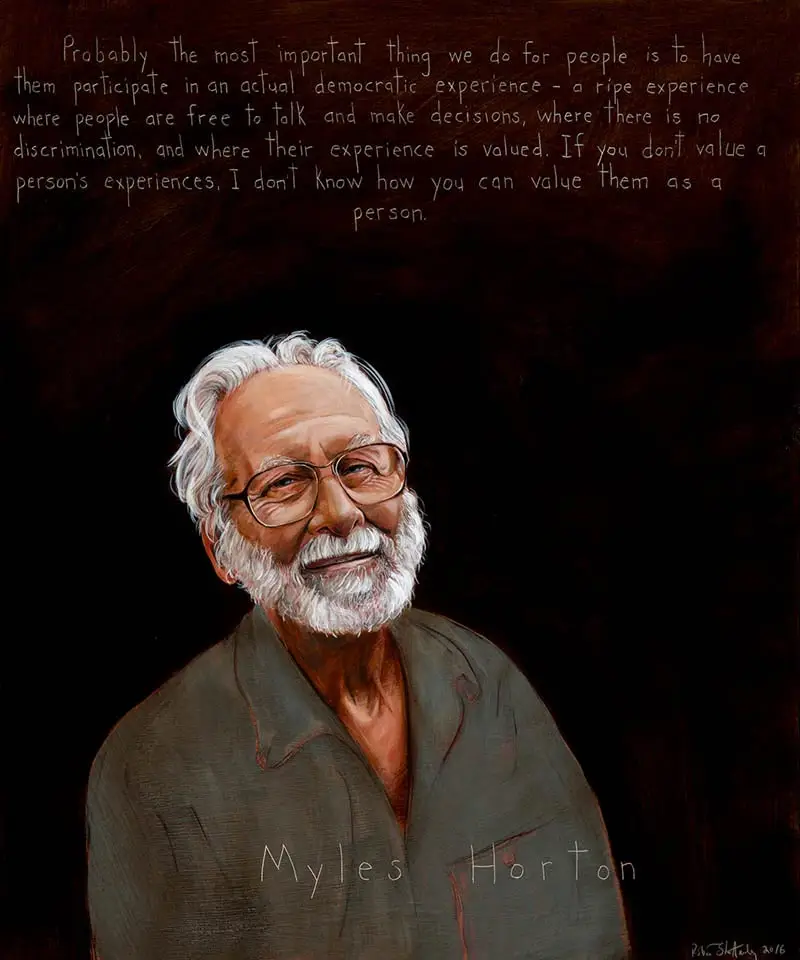

Myles Horton

Myles Horton

Educator, Activist : 1905 - 1990

“Probably the most important thing we do for people is to have them participate in an actual democratic experience – a ripe experience where people are free to talk and make decisions, where there is no discrimination, and where their experience is valued. If you don’t value a person’s experiences, I don’t know how you can value them as a person.”

Biography

“You can’t be a revolutionary, you can’t want to change society if you don’t love people.” Myles Horton’s love of people drove his career in activism through several decades and causes, from the workers movements of the 1930’s, to the Civil Rights movement, and through the environmental activism of the 1970s and ’80s.

Horton is best known as a leader of The Highlander Folk School, which he founded in 1932 with educator Don West and Methodist minister James A. Dombrowski. The three men shared a vision of a place where people of all races could work together to learn and share ideas. The Highlander Folk School was an important learning community for several truth tellers and heroes of the Civil Rights movement, including Anne Braden, John Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, among others. They gathered in Monteagle, Tennessee to study collective organizing and the power of groups to defeat injustice.

Myles Horton was born on July 9, 1905. He was raised in Savannah, a small town in west Tennessee, by his parents, Elsie Falls and Perry Horton. Both of Horton’s parents were teachers who also worked odd jobs, including in canning factories and sharecropping. The Hortons taught their son to be an activist and to see the value in all members of their community. In his autobiography, Horton wrote, “From my mother and father I learned the idea of service and the value of education. They taught me by their actions that you are supposed to serve your fellow men, you’re supposed to do something worthwhile with your life, and education is meant to help you do something for others.” Even when they were poor without much to eat, Horton’s mother would share food with other families in the community. Horton never got angry that he had less food to eat because he saw how strongly his mother believed in giving to others.

Eventually, Horton left home to study at Cumberland University in Nashville. He intended to study education and return to west Tennessee and open a school. Horton believed his best learning happened in the library, where he read books and formed his own ideas.

In 1927, he took a summer job organizing community meetings for the Presbyterian church, encouraging participants to tell their stories. It was excellent practice for the teaching he’d do at Highlander Folk School.

In 1928, Horton, upset that the college YWCA groups were racially segregated, organized a luncheon at a hotel for several local groups. When the black and white students arrived, they were confused, but they sat down to eat. The black servers told Horton they weren’t allowed to serve a mixed group of diners. He told them to ask the managers if they wanted to waste food for 120 people and not get paid. The meal was served. Horton knew it was a risk to violate segregation laws; any of the participants could have been arrested or thrown out of the hotel. But Horton wanted to do “something about a moral problem instead of simply talking about it…and over 120 people learned that they could change things if they wanted to.”

Myles Horton traveled the nation and the world, observing schools and thinkers that created change and empowered citizens. He studied at Union Theological Seminary and the University of Chicago. Later, Horton traveled to Europe. He was fascinated by the folk schools of Denmark, which had a strong influence on his ideas about education. In Denmark, he saw that social learning was more effective than book work. He summed up his thoughts on education this way: “Curiosity is very important I think, and I think too much of education, starting with childhood education, is either designed to kill curiosity, or it works out that way anyway.” Horton believed that education was best when it left room for students to develop and share their own ideas.

In 1932, Horton, West, and Dombrowski founded the Highlander Folk School on donated land in Grundy County, Tennessee. They believed that oppressed people were more powerful together. The school was a place for the oppressed to gather, learn, organize, and make change. Throughout the Great Depression, the school advocated for the working class by providing training for workers and labor organizers. Eventually, the school shifted its focus to Civil Rights. Throughout the 1950’s, the school organized literacy and voter registration for Blacks all over the nation. Rosa Parks visited and felt supported and encouraged by the community at Highlander Folk School the school just before her famous refusal to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. In 1964 the Freedom Schools organized by civil rights workers in Mississippi to give African American children and adults the opportunity of educational equality were modeled on the social justice schools developed at Highlander.

The fight for civil rights was long and difficult, with interference from the government and hostile community groups, including the KKK. Tennessee held trials, questioning Horton and trying to link him to communism. In 1961, the state of Tennessee forced The Highlander Folk School to close. Horton and his group organized and reopened the school in Knoxville.

Today, the Highlander Research and Education Center is a social justice leadership training school and cultural center in New Market, Tennessee, northeast of Knoxville.

Horton created an institution that has stayed strong for decades; however, he didn’t believe that institutions themselves deserved respect. Rather, they should earn respect by doing good work: “When people criticize me for not having any respect for existing structures and institutions, I protest. I say I give institutions and structures and traditions all the respect that I think they deserve. That’s usually mighty little, but there are things that I do respect. They have to earn that respect. They have to earn it by serving people. They don’t earn it just by age or legality or tradition.”

Myles Horton died in New Market, Tennessee on January 19, 1990. That year, his book The Long Haul: An Autobiography, was published, as well as a collection of conversations with Paolo Freire, We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change.

Programs

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

Education

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.